Better access to mental health services and bringing an end to “systemic and structural racism” and the stress that causes were pegged at a July 29 forum as two key ways to stem the high incidence of suicide among black youth.

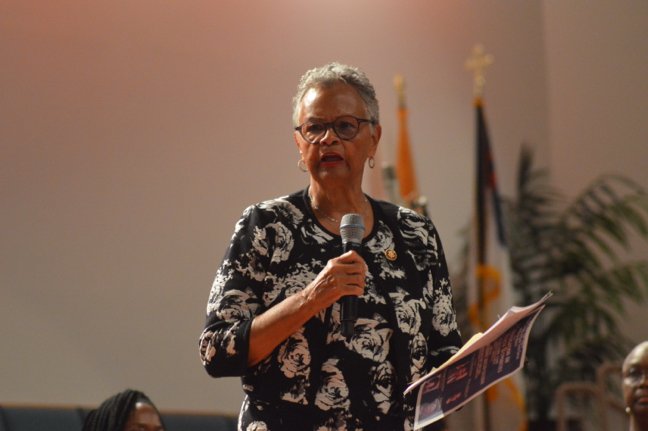

The panel discussion was held at the First Baptist Church of Lincoln Gardens on Somerset Street, and was sponsored by U.S. Rep. Bonnie Watson Coleman (D-12), a member of the Congressional Black Caucus’s Emergency Task Force on Black Youth Suicide and Mental Health.

In addition to Coleman, the six-member panel included Township Councilwoman Crystal Pruitt (D-At Large); state Assemblyman Herb Conaway (D-7); Michellene Davis, executive vice president of RWJ Barnabas Health; T-Kea Blackman, host of “Fireflies Unite with Kea,” and Kimme Carlos, executive director of the Urban Mental Health Alliance. The panel was moderated by Brittany Jean-Louis, founder of A Freeman’s Place Counseling agency.

Coleman said the “plan for this task force is to not only have our various meetings down in Washington, but other members of the task force are having coming-together gatherings in their districts.”

“We need to have conversations, we want to have conversations around the faith-based communities, we want to have conversations with teachers, with anybody who represents the front lines and parents and teachers and members of the clergy certainly represent that to our community,” she said.

Also speaking were Mayor Phil Kramer and the Rev. DeForest “Buster” Soaries, the senior pastor at FBCLG.

Kramer set the stage for the discussion, telling the nearly 200 people in attendance that the suicide rate of black youth aged 5 to 11 years has increased by 89 percent over the last 30 years, while the rate among white youth of the same age has decreased by 67 percent.

“So why is that happening?” Kramer asked. “Is it discrimination, is it lack of availability to health care, is it that the pressure is different for whites and blacks? Those are the kinds of things that haven’t been filled out yet, at least I don’t know that they have, and they are the kinds of things that need to be discovered so that we can stop this.”

Rev. Soaries suggested that the reason may be that this generation of black youth “seems to have lost the ability to say ‘yes.'”

“Thus we find young people without hope, young people who are giving up on themselves, young people who need a society to understand them and to serve them, rather than judge them and condemn them,” he said. “So this conversation is critical.”

Conaway said that although the statistics are troubling, this is “not a time to be crestfallen, it is a time to take action.”

“This is a space in which the governor needs to play a role to set the table for addressing these awful statistics, to try to understand them and develop a policy that will turn the tide so that we can save so many young lives,” he said.

“It is unclear what is causing these problems, but it seems to me that children are growing up in a time when the pressures upon them are unlike what many of us knew growing up,” Conaway said. “We haven’t, either within our family or our school systems, been able to develop a resiliency within our youth to protect them from the pressures they face today.”

With a nod to the Internet and social media, Conaway said teh world is open to youth in a way it had not been in past generations.

“That can be a force for good, but it can also bring in some terrible forces that can lead children astray and make them feel inadequate, lead the way to bullying and other very negative behaviors that result in tragic outcomes,” he said.

Conaway said schools should be one place that children could develop resiliency to these pressures.

One of the pressures the panel identified as affecting young black children is racism.

Davis said the African American community has “to be about the business of addressing systemic and institutional racism. Poverty was intended to be concentrated in communities full of black and brown people.”

“When we talk about what are the additional stressors, when we spoke about whether we have access to healthy nutritious food and whether we live in a safe environment, well, all of that is impacted undoubtedly by the systems and structures that were didactically formed in order to ensure the proliferation of the permanence of an underclass,” she said. “This did not just happen.”

Echoing one of Conaway’s thoughts, Davis said that it’s wonderful that the Internet lets young African Americans see “individuals who look like us” living in other countries.

“I can see what happens to individuals who look just like me in Ferguson, Mo., and Baltimore,” she said. “And what I see is the fact that individuals who look just like me are harmed by others who are supposed to serve and protect or by others who, quite frankly, are members of our own community, but I get to see it over and over again, and I get to see that there is no justice when it occurs.”

“So there is something that happens, an impact and an affect on our self-esteem, our self-worth, our value that gets eaten away at,” she said.

The panelists also addressed the refusal of African Americans to seek out mental health services to help deal with those stressors.

“What would be considered therapy for us would have been church,” Blackman said. “We didn’t have the proper coping skills to deal with that so not only is that trauma unresolved and gets passed down from generation to generation, now we don’t even have the coping skills to deal with that trauma.”

“When you think about the suicide rate among black children, they don’t really know how to deal with the stressors that they are going through, but the adults can’t deal with it either,” she said.

Conaway said that society in general is not getting adequate mental health care.

“I don’t care who you are, your access to mental health services is inadequate,” he said. “And you look at a person of color, their access is even less adequate.”

“When you grow up having to understand … this historic racism, what are you taught to do?” he asked. “You are taught to bear up, you are taught to bury your feelings, hold them inside and walk through the fire.”

Suppressing their feelings, he said, could be “a legacy of racism that has informed the way young boys are raised and their responsibilities to themselves and society. It is a negative feedback loop that saps one’s strength and leaves us vulnerable to some of these more drastic measures that some people take.”

Coleman said that the task force hopes to have a report out by the end of the year.

“The underlying premise is we’re not going to be here all day long for years,” she said. “We have to come up with our findings, our solutions, our recommendations, whether they are grant funding, legislation, policy, whatever.”

The Franklin Reporter & Advocate Eight Villages, One Community

The Franklin Reporter & Advocate Eight Villages, One Community