By Mark Grieco.

Several years ago, I happened upon a tour of one of the preserved, 18th Century farm houses in Franklin Township. A costume-clad guide explained the various artifacts of the house to an interested couple, the only other people on the tour. After the couple wandered to another room, I played upon a hunch and in a confidential whisper asked the guide, “Where did they keep the slaves?” In truth, I had no idea if slaves were part of the history of that house. But the guide looked around to see if the other visitors were out of sight, and then mutedly pointed to the attic. Well, that wasn’t in any tourist info I’ve seen about Franklin.

The best-known version of Franklin’s early history tells of how white pioneers, especially the Dutch, came to the Raritan Valley and by their own industry and thrift carved out of the wilderness a settlement of neat, prosperous farms and villages. That is the version most people are familiar with, but in fact it is a half-truth. In reality, many early white settlers of Franklin were slave owners who benefited financially and politically from that enslavement.

For those who are not familiar with the reality of our township’s history, or mistakenly believe slaves were only in the South, I refer them to that excellent tome of truth and facts, Franklin Township, Somerset County, NJ: A History by William Brahms. In his book, Brahms, once a Franklin Township librarian, states quite plainly that in colonial Franklin many white farmers who owned farms of 100 acres or more – at least 75 percent of the farms were that size – owned slaves, to clear the land of forest and to farm it. Both Black and Native-American slaves were used.

Brahms’s book contains three lists pertaining to slavery in Franklin: one regarding slave manumission, one a cobbler’s list, and another a list of 19th century Franklin taxpayers and their “assets”, including the number of slaves they owned. The first two lists contain the names of both slave owners and their slaves. The names of slave owners reads like a Who’s Who of early, prominent Franklin families. The family names are quite familiar to anyone who has even a passing knowledge of local history, roads, or farms.

Brahm’s book also contains a list of early Franklin elected officials where you will find some of the same family names on the three lists mentioned above. To be fair, Franklin had a small rural population for much of its history, and some names will consistently pop up regardless of the historical situation. It is not my goal to embarrass the living ancestors of slave owners, but it would be reasonable to assume many a white family in the township was put on the road to prosperity by the toil of slaves. And I have observed financial success has rarely been an obstacle to political influence, particularly when holding office is limited to white, land owning, males.

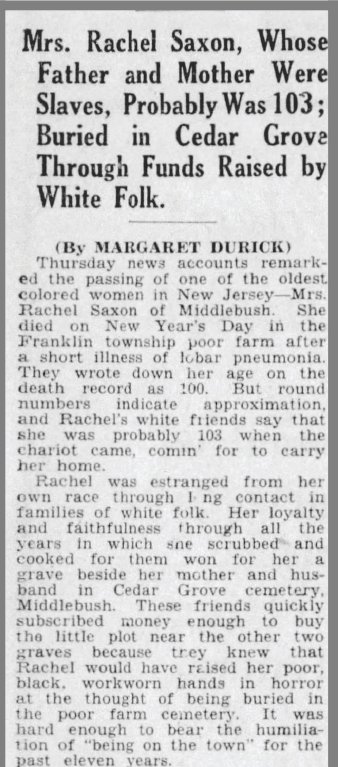

Many local historians and writers besides Brahms told the truth about slavery in the township. Successful farming, according to Nineteenth-century Franklin historian Judge Ralph Voorhees, depended on how rapidly the land could be cleared of forest. To do that, white farmers in Franklin used slaves. The death of 103 year old Rachael Saxon of Middlebush, daughter of slaves and married to a slave, and probably a slave herself at one time, was covered by the Daily Home News in 1930 in typically racist, paternalistic language of that period.

Saxon, who was “moved” to Middlebush 80 years before her death, died at the Franklin Poor Farm on what is now Gates Road. She was buried in the eastern section of Cedar Grove Cemetery, near her family’s graves as close as memory would allow, since both her husband’s and mother’s graves did not have markers. Four years before that, the Daily Home News reported on a 1733 meeting of New Brunswick’s first city council (a section of the city was part of Franklin until it was seceded by the state in 1850). One of their first ordinances enacted was called “For Regulating Indian Negro Mulatto Slaves in the night Time” and required slaves out at night to either have a lantern or a note from their owners,or face apprehension and jail. In a 1988 presentation to the Franklin Township Historical Society, Dr. Peter Wacker is quoted in the Franklin News-Record as stating, “The Dutch settling the area were using slave labor to work very large farms with very good soils. It was an affluent area.” He further stated, “The large amount of slavery in Somerset County, was directly connected with the large Dutch population and huge estates.”

Historians and journalists have illuminated Franklin’s slave past, but perhaps because the truth is unpleasant, the more sanitized version of the township’s settlement has become the dominant one. But it is time for the ascendency of the truth: Many of the white settlers of Franklin did not single-handedly create the wealth and influence they passed on through the generations, it was built in part by the sweat and blood of slaves, many of whose names, contributions, and even final resting places are now unknown. I urge future statements by the municipal government about the township’s history to make this fact clear. A good place to start would be the “History” page of the township’s official website, where there is no mention of slavery at all, but only Dutch settlers. Township partnerships with historical preservation groups regarding historic homes and properties in the township should include research and publication of the contributions of slaves associated with those sites, not just their white owners. And while there are numerous preserved structures celebrating Franklin’s past, nothing tangible exists recognizing the life and labor of slaves. Slaves in the attic are part of Franklin’s past, and the honest recognition of the lives of those slaves matters if we are to have a clear understanding of the turbulent times we find ourselves in now.

The Franklin Reporter & Advocate Eight Villages, One Community

The Franklin Reporter & Advocate Eight Villages, One Community